August 30, 2023

In the first part of this series, we took a look at developments on the battlefield, and discussed strategies and problems the Ukrainians have encountered. My overall conclusion is that the offensive proved to be costlier, slower, and more difficult than anticipated, but that ZSU adjusted its strategy and is making steady progress. The have about a month to go before rasputitsa makes operations difficult, and have decent chances of reaching Tokmak, at the very least. If this assessment is correct, the war will continue with the initiative shifting to the Russians for the fall/winter season. ZSU’s strategy will be to deny them more gains as they prepare for their 2024 offense, which hopefully will not be delayed as this one by sluggish Western help. I expect the Ukrainians will start receiving American Abrams tanks, as well as long-range missiles like ATACMS and Taurus, cluster munitions for HIMARS, as well as increasing domestic production of ammunition, equipment, and drones.

The fall/winter season, however, is likely to be quite tough because ZSU will have expended quite a bit of their 155mm ammunition (including the vast amount that South Korea seems to have given them — I guess the unexpected mid July Kyiv visit by President Yoon Suk Yeol was productive.) The Western facilities for shell production have been ramping up but probably will not be able to start delivering the necessary amounts until spring/summer 2024.

Western Ammunition Production

The US has made deals with Bulgaria and South Korea for the production of 155mm shells for Ukraine, and is negotiating a deal with Japan for the same. Ramping up domestic production takes time (it will go from 14,000 155mm shells per month before the war to 90,000 per month by 2025). As of this year, US and six of the European ammo makers are producing about 1 million 155mm shells per year, but by 2025 this figure will be at least 2.5 million, of which less than half will be from the US.

This is the largest increase in ammo production in the US since the Korean War, and it is being accomplished in three ways:

- adding shifts to the government-owned production facilities: they used to run for 8 hrs/day before the war and will run for 24 hrs/day, every day

- upgrading existing facilities and building new ones — this takes time, but the US government has already issued billions dollars worth of contracts, which fund a new plant in Texas (with 2-4 planned for the future) as well as expanding metal parts production lines in Canada

- contracting with private industry to build 155mm shells in their own facilities — this is new since until now, production in government-owned plants managed by private contractors was considered sufficient

In Europe, there are the major players:

- Germany’s Rheinmetall (which acquired Spain’s Expal), currently producing 450,000 rounds per year and projected to reach 600,000 next year — its CEO said that, in theory, his company could provide 60% of the ammo Ukraine needs. The expansion is mostly due to new production from their plant in Australia, which can make up to 100,000 shells per year

- Chechia/Slovakia’s CSG, currently making 150,000 shells per year

- Sweden’s Saab said that it can produce 400,000 per year by 2025

- Britain’s BAE Systems makes about 30,000 shells per year, but has received contracts from the UK government that will ramp it up eight-fold, so up to 250,000-300,000 per year (not sure of target year)

- Poland’s PGZ/Dezamet makes about 40,000 per year now but has contracts to ramp up to 200,000 per year, and the funding will pay to produce at this rate for 5 years

- Norway/Finland’s NAMMO produced up to 20,000 per year before the war, but are scaling up to make 200,000 per year by 2028 — it is the only manufacturer of the ones listed whose production will not be online by 2025

- Bulgaria got $402 million, which could buy as many as 800,000 shells at $500 a piece (probably fewer once s&h are included)

- France’s Nexter makes 50,000 (an increase from 15,000 per year before the war) and is ramping up to 100,000 by 2025 — its production was for domestic use but the company said that the expansion was needed to meet European orders for Ukraine

The bit about Nexter illustrates an important caveat to keep in mind: not all of the production will go to Ukraine, of course. In fact, in the French case they seem to be donating about 24,000 per year only, at least for now. Some of what’s being made is going into replenishing and augmenting stocks of 155mm ammo in Western countries. Also, I do not know how many of these are going to be (the much more expensive) precision-guided versions.

Ukraine is estimated to fire up to 3,000 artillery shells per day right now, which is a decrease from the earlier days of the offensive when it was doing massive shaping operations and use could easily double or even triple. At, say, 5,000 average per day, it will need 1.8 million shells per year, which the West can handle.

Also, none of this includes the (vast) stocks of 155mm in Asia (Pakistan, South Korea) and the existence of production facilities there. US contracting with ROK and Japan shows these possibilities. Although, as mentioned above, South Korea might have supplied a very significant number of shells for the current offensive, and this delivery might not be repeatable.

Finally, we are only talking about 155mm shells here, which are a fraction of what Ukraine uses even though their share will increase as ZSU transitions to NATO standards and replaces Soviet-era (and compatible) inventory. Ukraine has ramped up domestic production, and just recently announced the opening of a second line to make mortar rounds.

Even under the most fanciful figures I have seen for Russia, its production/refurbishment cannot come anywhere near this, which is why they are burning through their Soviet-era stocks like there’s no tomorrow. Credible estimates put Russia’s annual production at about 1.1 million shells of all types annually.

The Russians are, of course, trying to increase their production as well, but the sanctions are making this less than straightforward. Moreover, it looks like the Europeans have finally understood that they cannot depend on the US for their security entirely. One evidence for this is their worry that the 2024 presidential elections might cause the US to decrease its military aid to Ukraine, which is one reason the EU Foreign Ministers are holding an informal meeting in Toledo, Spain tomorrow (the other is the coup in Niger). The EU is pushing for increasing aid to Ukraine. While the medium and long term prospects for Russia to outproduce the West are nonexistent (even with North Korean and some Chinese aid), the immediate future is more concerning. The current rates of Western production are insufficient to offset the advantage of enormous, if rapidly dwindling, stocks of Soviet-era ammunition that Russia can throw at ZSU.

The only immediate large-scale source of munitions under direct control of the West (as opposed to having to negotiate deliveries or buy it outright) is the stockpile of cluster munitions in the USA, which can be used to bridge the gap between current needs and future production.

Why the US Should Have Sent Cluster Munitions to Ukraine Yesterday

As you know, I’ve been arguing for sending Ukraine cluster munitions since January this year. I got slammed as a warmonger over this because many nations — USA, Ukraine and Russia not among them — have agreed not to use them because of deleterious effect on civilians. We have now given Ukraine some (I don’t know how many) after significant delay due to politics. So what was/is the problem?

First, the objection to DPICM (dual-purpose improved conventional munitions) rounds is based on the fact that early versions had a very high dud rate (they fail to explode) and so remained dangerous long after they were dropped. Civilians would accidentally detonate them, causing significant harm. The Russians have been using DPICM in Ukraine and have a huge stockpile. Indeed, Shoigu lied that they had not used any and threatened to use them if ZSU did not stop — you will see below why. The Russians are using them sparingly not because they care about civilians — the have made Ukraine the most mined country on Earth, and landmines are a lot more dangerous to civilians — but because their DPICM arsenal consists of old rounds with a very high dud rate, making them essentially ineffective. ZSU has been using DPICM supplied by Turkey, which has better characteristics, and the ones we are giving them are even better. Initially, the dud rate could be between 5% and 30%, but between 1998-2020 the Pentagon tested the newer versions and concluded that the modern DPICM’s average dud rate is under 2.35% (range between 2% and 6%). In other words, the objection is hardly valid and the Ukrainians need to weigh the effectiveness of these rounds against the potential risks they could pose.

Second, unlike the single-purpose 155mm stockpile we intend to use ourselves, the US government had decided to retire DPICM, and has been destroying or converting them for years. This process paused a few years ago and we appear to have about 3 million rounds in our stocks (per March 21 2023 Congressional letter demanding that Biden deliver DPICM to Ukraine). In other words, we are sitting on an enormous pile of munitions that Ukraine desperately needs and we will not use at a time when procuring single-use 155mm is very hard because US/EU production needs time to ramp up. This is why I’ve been arguing that DPICM should be sent as a stop-gap measure while the capacity goes online.

When the Biden administration finally OK’ed the delivery of DPICM, experts understood how effective it could be on the battlefield — after all, this is why they were developed in the first place. But by all available information, they have exceeded even these expectations. While not some kind of Wunderwaffe that would win the war for Ukraine, they have been transformative on the battlefield, much like HIMARS and Storm Shadows provide to be. Let me cite one of the Russians on the receiving end of Western DPICM:

“…we are in real colossal difficulties. […] One cannot fail to take into account the effect of modern Western cluster munitions — they turn into mush both soldiers on the frontlines (and not just there) but also civilian infrastructure in the rear. […] We should have spent all our efforts on blocking the delivery of cluster munitions to Ukraine: promise that we would not use them either, split the Europeans who ban their use. We had a chance. But instead they took us for being weak, and we gleefully took the bait and declared that we have so many of these munitions that they are hills instead of stocks. Yes, we have lots of them. You can find photos. But basically, lots of time-ravaged things we failed to destroy, and the rest — technically obsolete. And with the delivery vehicles not everything is good.

Now we can’t roll that back: when you were caught being weak, trying to scare them with “being twice not weak” is silly. The General Staff already know this, but can’t communicate this upwards, there’s no decision. The guys on the frontline take the rap, and it’s very hard. When we have problems with medical help, those wounded by cluster munitions die more often, and it’s a terrible painful death. The enemy has learned (imagine that, they are also learning!) to cut off escape or supply routes with artillery, and trenches can’t save you from cluster munitions. You can’t save yourself with bandages and tourniquets: after cluster use you need fundamental medical help, if you live through it. In the trenches, a mess of the living and the dying is formed, and the dying often can’t be helped.

In these cases, the enemy methodically waits for our units that rush to help their comrades. I’ve seen all of this in Chechnya, where a sniper would leave a wounded soldier in order to attract more guys on him. But then it was individual work, and here — with the cluster munitions it’s the same but magnified tens and hundreds of times. We need counter-battery fire but we don’t have it.”

Colonel Shouvalov, VSRF

I do not think commentary is necessary. Cluster munitions are so effective that Dan Rice, the US artillery officer who briefed General Zaluzhnyi on DPICM last year estimated that after Turkey supplied them to Ukraine last year, “Russian casualties surged from approximately 5,000 per month to over 20,000.” He is now arguing that we send M26 MLRS rockets to Ukraine. These are cluster munitions with 30-50km range and can be fired from HIMARS. The best (or worst, depending on perspective) of both feared weapons. Ukraine has now requested them from General Milley, the Chair of JCS. Ukraine has compiled a report on the effectiveness of DPICM, and if it shows anything remotely to what the Russians are talking about, it might be prudent to revisit our decision to stop making these munitions.

With all of this, we need to take a closer look at Russia’s war-fighting potential with the caveat that we do not know what agreements Russia has concluded with North Korea about military aid. We have seen evidence of NK-sourced shells in use, but it likely came from Iran. I already touched upon the shell production, so let’s turn to the one thing that everyone agrees Russia can always outcompete Ukraine: manpower.

Russia’s Mobilization Troubles

The Kremlin has repeatedly denied rumors that it is preparing a second over round of mobilization. I say overt because the original mobilization decree from last September is still in effect, and the military has been steadily taking people to the tune of about 20,000 to 25,000 a month (earlier estimates put it at 50,000 per month but I am having doubts about that). The tempo is not sufficient to cope with the massive losses on the front, with casualties that can top that monthly draw since the introduction of American DPICM in July. Wagner relied on prisoners for its meatgrinder attacks on Bakhmut, but this is a finite (and low-quality) resource. The demand for men is outstripping supply, at least voluntary supply, in Russia, and we have lots of evidence for this.

First, the Russian government has been furiously adopting legislation to curb the dodging of military summonses. As of July 25th, the Duma passed or proposed laws that:

- impose a fine of up to 500,000 rubles for failing to cooperate with the military recruitment office when mobilization is declared

- impose a fine on companies of up to 400,000 rubles for failing to submit lists of citizens eligible for the draft when their initial records are being made

- impose a fine of up to 30,000 rubles for failure to show up after receiving a draft notice

- increase the higher upper age limit of 30 years for draft eligibility (effective Jan 1 2024); earlier they had been talking about a phased-in introduction, and increasing the lower bound.

- forbid citizens from leaving the country from the moment their draft notices are registered as served (recall that earlier the Duma passed a law under which a notice is considered served when sent electronically to the citizen’s account with the government service portal)

- limit the right to drive for people who have failed to answer their summons

- allow draftees to sign 1-year contracts for military service

The saga with the age of eligibility is instructive. On March 13 this year, Russia’s parliament began considering a law that would shift the age of men eligible for the draft from 18-27 to 21-30. The explanation was that it would allow people who wish to go to the university to do so before serving. I was very skeptical of this because to my mind, the only reason to muck around with the age limits is to increase the pool of eligible men, which is what Russia needs. I thought that perhaps there were some complex demographics that would yield a larger pool through the shift.

It turned out a lot more prosaic. On July 21, the Duma did alter the age of eligibility… by moving the upper bound to 30 but leaving the lower bound at 18. Instead of a 9-year window, they now have a 12-year window to play with. The Duma did not elaborate why it chose to expand the upper limit without shifting the lower one but one guesses canon fodder right now is more important than people with college degrees. A great sign for the future of Russia.

The Duma also increased the age for men subject to reserve duty to 60. Putin then signed a law that expands the upper age limit for recall of reservists by 5 years: category I to 40, category II to 50, category III to 55, junior officers to 60, and senior officers to 65. Truly, “only old men go into battle,” as the old movie had it.

The Duma’s clarification that draftees will be able to sign 12-year contracts (to get the higher wages described below) also has an important caveat. Contracts for 1 year are only available to those who have previously served. For new recruits, the contracts will be 2 years or more. This bit of information came straight from a video of military recruiters who were making a pitch for volunteers at a factory in Tolyatti. Here are the highlights:

- contracts now are at least for a year or more, and people who have not served before will start with 2 year contracts

- due to the “circumstances in the country,” contracts are not terminated but automatically extended

- anyone between 18 and 65 years of age can sign up

- nobody would be sent immediately to the trenches “on the territory of the special military operation” but instead will go for training for +/- 3 months

- “everyone will get to hold a rifle in their hands, everyone will get to bounce in and out of trenches, so to speak” (this is a direct quote, shooting apparently optional, learning to conduct combat operations, also — this screams cannon fodder)

- salary is 195,000 rubles, with 200,000 sign up bonus (more on what these numbers mean below)

- there are “very serious problems with labor pool” in the city, and “there are not enough workers for anything”

- people should ask relatives and friends if anyone wants to serve, and remember that only now you will be able to choose where to spend your time serving

- hey had recruited about 250 men, which is 10-15% of the regional quota, and if this was not rectified, there would be a second wave of mobilization

- the situation is serious, which is why they are going to all factories, but the step is forced by circumstances

Medvedev was bragging that mobilization is going according to plan (over 240,000 this year to date). This makes me doubt his statement. Tolyatti has a population of about 680,000. The recruitment quota for the voluntary contracts is apparently somewhere a bit over 2,000. They have managed 1/7th of it. There is no reason to think that Tolyatti is an outlier. Indeed, with AvtoVAZ, the larger employer there, getting nationalized, they should have no labor shortages.

Every round of recruitment meets with more resistance because previous rounds have already scraped the people who couldn’t or didn’t want to avoid it. Hence higher salaries and bonuses. But this seems to be insufficient, since scarce labor probably means higher wages as well.

Russia cannot avoid a second mobilization wave. This here suggests that it might not be possible to do it on the q.t. either. Russians are not going to the front with enthusiasm, and it is increasingly difficult for regime to make up the losses it’s suffering at the front. The desperation of the recruiters is obvious. Think what this does for morale of people they are talking to. Some of them are bound to be asking, why is it that the government is constantly demanding more men when everything is fine and SMO is going according to plan? What happened to all those men that already went?

I am also beginning to wonder about the huge numbers reported in Ukraine, especially in the north. I explained their non-presence at the front with strategic military considerations… but maybe part of that absence can be explained by the numbers just not being there?

Just to add insult to injury, the Duma also recently clarified that draftees will be “permitted” to go to the front after one month of service. “Permitted,” indeed.

The second indicator of trouble is that the Kremlin has increased wages and compensations for death or injury on the front to unheard-of levels. According to Volya, the changes are as follows (figures are in rubles):

- before the war: 26k-86k/month for privates/juniors, 116k-242k/month for officers

- after mobilization: 204k-232k/month for privates/juniors, 272k-522k/month for officers; all get a one-time signup bonus of 295,000 from federal/local budgets (the billboard in Moscow region in the photo advertises a salary of 204k/month with a signup bonus of 695,000 — this includes the 195,000 from the federal budget and 500,000 from the regional — as one would expect, for the rest of country the regional payments are smaller at just 100,000).

- mercenary units: 290k-450k/month depending on experience, 580k/month officers

Thus, wages have more than doubled for officers, and have increased up to 6 times for soldiers. For comparison, the monthly income in Moscow is 137k and in Privolzhie it is 52k. The median is 95k/month (about $985 at current exchange rates). The military salaries are therefore highly attractive for average residents even in the rich regions, let alone the poorer ones where they can be several multiples of mean income.

These salaries are not retroactive, which has created a lot of tension between the newly mobilized and soldiers who have been fighting in Ukraine under old contracts. Volya reports that sometimes up to 70% of the salary of the new mobiki is confiscated, and that there are fights and even sometimes murder over the disparity.

The increases were designed to tamp down on the discontent that the Kremlin expected after declaring mobilization. The soldiers compensated well, which means they do not complain until they end up on the front in Ukraine (and by then it’s too late). Because the staggering level of losses the Russians are suffering does not filter down reliably, it appears that many men and their families see enlistment as a way to score the quick buck and improve their financial situation.

For those that do not make it back, the families are kept quiet with generous compensation as well. The total paid to the family of KIA soldier is between 12,500,000 and 15,500,000 rubles — the equivalent of what an average 29-year old man can expect to make by the time he retires at 65. This insane level of compensation is partially sustainable only because the payments are made when the bodies are collected and positively identified, which is about 50% of KIA/MIA. The spouse of KIA/MIA also receives a pension, additional monthly payments for child support, up to 60% assistance with utilities, and preferential treatment for various social services. For WIA, the one-time compensation is 1,560,000.

Given the standard of living in Russia, the government’s generous payments have effectively dissipated social discontent that might have arisen already over the war. This suggests that budgetary troubles might become a lot more consequential if they undermine the Kremlin’s ability to keep up with these outlays.

Volya estimates that the federal budget could handle about 1-2 years of this, all else equal. But of course, not all else is equal. They do not seem to have factored in the expected fall in revenue due to sanctions, as well as the fact that transitioning more of the economy to wartime footing is going to decrease government revenue further as other taxable economic activities decline. With more people mobilized for the war (there are about 600k now in Ukraine), the economy will be affected even more.

For their calculations, Volya estimates that Russia continues to mobilize about 48,000 per month but losing 12,000 KIA and 27,000 WIA over the same period. (With subpar medevac, many of the WIA cannot return.) Thus, the net increase in troop numbers is about 9,000 per month, and these have to be trained before being deployed anywhere where they would make a difference. As we have seen, however, these estimates of new recruits might be inflated. This means the fiscal burden would not be so high until mobilization picks up.

Third, when coercion and bribery don’t work, recruiters are resorting to dirty tricks. Colleges in Ingushetia (Russian Federation) required graduates to come in person to receive their diplomas. When they did so, they were handed summonses in front of witnesses. They had to either accept to go to the front or refuse, in which case they faced a 500-3,000 ruble fine if this was their first refusal or 200,000 ruble fine, forced labor, and imprisonment for up to 2 years of they had refused before (and no diploma). Ingushetia is among the poorest regions in Russia. A recent study correlated the verified, by name, deaths of Russian soldiers (over 20,000) with their origins and found — to no one’s surprise — that they come disproportionately from the periphery while Moscow and St Petersburg have been largely spared. A new official wave of mobilization will not spare them again, and this will increase social discontent.

The quality of life in Russia being what it is, however, it appears that if the Kremlin can pay enough, a lot of Russians will be content to go to war for Putin in order to buy themselves a better life (provided they survive).

Russia’s Economic and Fiscal Troubles

The Kremlin continues to depend on revenue from energy exports. So let us take a look at what its oil exports are doing for starters.

Exports of Russian oil dropped by 25% after Putin demanded that the discount be decreased. The Russians tried to reduce the Urals discount from 30% Brent to 20%, but as a result China and India cut their purchases by nearly 1 million barrels/day. As befits a true friend and partner, Iran immediately began to displace Russia on the Chinese market since without the discount, the Russian oil would not be competitive. In fact, since mid May, Russia’s sales of oil in Asia (China and India, mostly) has decreased by 25%.

Even the decrease in discounts is not as impressive as it sounds. The chart below says “Russian Urals oil returns to pre-SMO levels” but of course denominates the income in rubles. Thus, in January 2022, it was 6,460 rubles, and now it’s 6,510 rubles. The nuance, of course, is that in January 2022 the dollar cost 76 rubles, and now it costs 97 rubles. In other words, the “recovery” is just an artifact of the weakening ruble, which masks the effect of the discount (which is clearly visible in the continued difference between Brent and Urals).

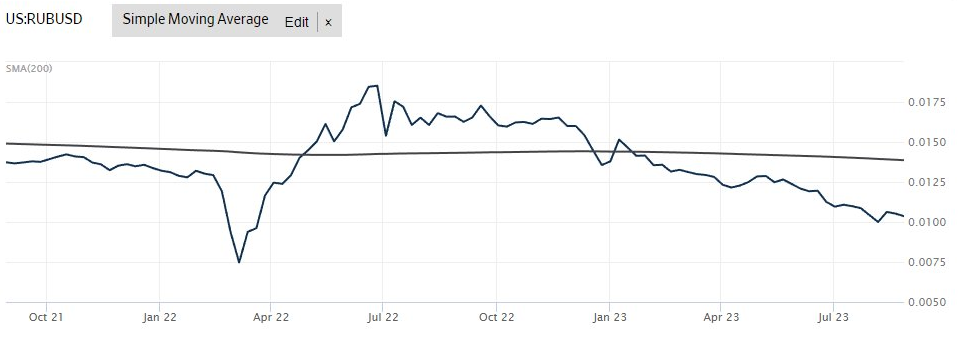

Speaking of the ruble, in early August its fall became noticeable and the Russian Central Bank (CBR) announced that it would not intervene to prop it. This occasioned an angry outburst by Russia’s premier propagandist Solovyev who demanded to know why the ruble is weakening, why people are getting poorer, and why nobody in the government seems to be able or willing to do anything about that. He also complained that the world is laughing at the ruble as it is the third weakest currency in the world (he was referring to claims based on this article).

The ruble has been steadily falling since its peak in the summer of 2022 when capital controls and large demand for gas and oil (among others, by Europeans desperately trying to fill their stores in anticipation of the sanctions that were coming online at the end of that year) had driven its recovery from the invasion shock in February. Since the start of this year, something interesting has been happening: the price of Brent has gone up (per previous chart) and yet the ruble has continued to decline. Usually, when oil becomes more expensive, the Russians get more foreign currency, which they use for various purchases, driving up the value of the ruble. The fact that the ruble keeps falling despite oil prices going up means that the Kremlin is unable to reap the usual benefits.

The CBR forecast that the Russian economy would lose 30% of its export revenue in 2023. Only about 34% of the Russian exports are now in dollars or Euros (27% are in currencies of “friendly countries” which can only be used to purchase goods in the respective country, and 39% are barter — denominated in rubles), which means that it can expect only about $140 bn this year, which is a fall back to 2003-04 levels.

Solovyev’s rant was probably indicative of public moods, and as the ruble began to approach the fateful 100 rubles per US$ threshold — an exchange rate that would remind too many Russians of the painful 1990s), the CBR’s resolve weakened. When the ruble suddenly tanked to 102 for US$, the Kremlin demanded that the CBR intervene to recover its value and stabilize it (August 14). The Bank did this with a vengeance. Analysts had expected that CBR would not raise the 8.5% rate above 10%, but it went to 12%. While it is likely to prop the value of the ruble in the short term, it is unlikely to arrest its overall downward trend while the war continues as the weakening is driven by the deficits arising from war spending. The cuts to social spending can only get the Kremlin so far — and will be very unpopular — so the deficits will widen, further increasing the temptation to print rubles. Vanity projects like sending a rocket to the Moon — especially after its dismal failure — would look like a sign of bad governance rather than an occasion for national pride next to dwindling paychecks and worse services. The Russians might be used to a low standard of living outside the premier cities, but this is not going to spare anyone.

While the Russian economy will not “collapse” as many want it to, it will continue limping along in a much diminished state, going from bad to worse until it bottoms out somewhere. Where, nobody knows, as it partially depends on our willingness to enforce the sanctions. (It was recently revealed that the Russians have found loopholes in the energy sanctions by over-charging for transport and using mystery buyers that has allowed them to circumvent the cap and generate something like $1.2 billion extra over 3 months from sales to India alone.)

Among the signs of growing strains:

- Russia’s (known) 2023 military budget of 5 trillion rubles ($52 bn) was spent by the end of July. The government is projecting that it will spend 9.7 trillion rubles ($101 bn) total by the end of the year. This is a third of the budget that we know of. Most financial and economic data coming from Russia are curated and likely fake as they made almost all relevant indicators secret last year.

- Putin signed a decree for a one-time 10% tax of excess revenue for large companies. There was a similar tax last year, which seems to indicate that it is not a “one-time tax.” The ratchet effect in taxation during war is merciless.

- In April, 35% of Russian companies said they had trouble with labor shortages. By August, this became 42% of the companies. As I’ve noted before, the low unemployment that Putin likes to brag about really means trouble with supply of labor due to three factors: (1) mobilization, (2) emigration, and (3) demographics.

- The Russian government decided to suspend, until the end of the year, purchases of foreign currency (e.g., yuan and gold) for the Sovereign Fund with the excess revenue from sales of oil and gas, as required by its budgetary rules. The reason is that doing so would weaken the ruble even more. Instead, excess revenue would be redirected to the budget to finance the deficit. It is unclear what amount is being talked about here. The CBR started selling yuan from the Sovereign Fund on August 1 to prop the ruble again.

- The Finance Ministry proposed imposing an 8% export tax on raw materials until the end of the year, expecting that this would bring into the budget 87 billion rubles.

The “progress” in economic growth the Kremlin touts is driven by spending on military equipment, which you can neither eat nor use to deal with your health problems. Like the “very low unemployment” they regularly trot out, this is an indicator of serious trouble — with nearly half of Russian companies reporting that they are unable to find workers, the low unemployment is merely labor shortage due to a combination of a demographic squeeze, emigration to escape mobilization, and mobilization for the war.

And even their military-related production is running into trouble. One recent analysis of activity at the Armor Repair Plant BTRZ-103, which had received a contract to modernize 800 T-62 tanks over 3 years (so about 22 per month), is managing somewhere between 7 and 17 per month (the latter is very generous). In other words, at this plant, their actual output is between 23% and 69% below target. The situation with the other six known such facilities is even more dire. The current rate of destruction of Russian MBTs by ZSU exceeds the repair and production capacity at this point — which means the Russians would have to redirect even more of their dwindling income if they wish to compensate.

Unlike Iran, which is after all at peace under the sanctions regime, Russia is fighting the largest war in Europe since WW2. The outlays are massive, and so the place where its economy bottoms out is going to be far worse. Maybe not North Korea bad, but bad.

The upshot is that it would have to create significant pressure on the elites to end the war somehow. Whether they can move Putin to do so is doubtful. But he should be looking increasingly nervously at people around him the longer this goes on. This brings me to the last section of this part of the update: Putin’s security.

The Kremlin Tightens the Screws

In the aftermath of Prigozhin’s mutiny, the regime in Moscow has moved to reduce threats, real or imagined, to Putin’s rule:

- Wagner PMC. The dismantling of Wagner both in Russia and abroad culminated with the murder of Prigozhin and Utkin (as well as other top Wagner people) when their flight from Moscow to St Petersburg blew up in mid-air on August 23.

- Wagner sympathizers at MOD. General Surovikin — potentially connected to the mutiny — was fired from his post as commander of the Air Space Forces (VKS).

- Officers critical of the conduct of war. In a prominent case, General Popov was dismissed from command in Ukraine and sent to Syria.

- Popular figures critical of regime. The most notorious of them all, war criminal Girkin, was arrested and denied bail.

Wagner Opera Whodunit. Prigozhin’s demise was met with a shrug: it had been the most anticipated and predicted event since the former cook folded at the peak of the mutiny. Everyone scrambled to assert how they had known that Putin would have him killed. Of course, the same people rarely commented before the assassination on several odd facts. For instance, while several thousand Wagner soldiers did go to Belarus (where they apparently are training Belarusian forces), Prigozhin himself repeatedly showed up in Russia, where he was busy dealing with his rapidly dwindling commercial empire. While the vultures were circling his assets, massive transfers to his companies continued. Companies connected to him somehow managed to obtain government contracts for at least 2 billion rubles in the month since the mutiny. This might have been done to keep the indirect financing of Wagner in Africa, where their replacement by MOD-loyalists is underway. I had speculated in my analysis that while Wagner will be destroyed in Russia (as has happened — its members who stayed there signed up with MOD), the Kremlin would keep them abroad because they have been so useful there. However, judging by African leaders who suddenly refused to meet with Prigozhin or Wagnerites despite previously being extremely friendly with them suggests that the Kremlin has been making offers they can’t refuse. Wagner’s empire in Africa is nearing its collapse, and Wagner forces in Syria have already been mostly disarmed.

In other words, there were clear signals that the Kremlin is eradicating Wagner. I do not know what Putin promised Prigozhin and the Wagnerites during their meeting on June 29 at the Kremlin. (Putin is supposed to have druly remarked, “You got your wish. You made it to the Kremlin.”) But whatever it was, it seems to have convinced Prigozhin that he was going to make it out of this mess alive, possibly with a substantial, if much diminished, fortune. And this is why the now-accepted narrative that Putin killed him bothers me. It just does not add up.

Assume that Prigozhin was not the idiot that virtually the entire Twitter expert analysis makes him out to be when they say it was 100% certain Putin would kill him. He had survived, and prospered, for years in a very cutthroat world. His top henchmen were with him on the plane, and the more people one requires to be idiots for the explanation to work, the less plausible it gets.

From the moment the mutiny went off the rails (Putin declaring against him), Prigozhin must have known he was toast and desperately needed a way out. He would know Putin would love to have his head on a platter. Continuing also meant a highly likely death, but offered a small chance of success if others joined him. So only reason to stop the mutiny (also very likely ends with his death but there’s a chance it would not), is some reason to believe he would have better chances if he stops.

But how can Putin credibly promise not to kill him when he’s weakened by abandoning the mutiny? Wagner being dismantled in Russia after that was a near certainty, so Prigozhin’s position could only get worse with time. Even in Africa, as we have seen. Any thought that he might have been “useful” to Putin somewhere (Ukraine/Africa) would be put to rest by this, so this cannot have been the guarantee — at the very least he should have been making himself scarce in Africa the more obvious it got that he’s being sidelined. Instead, he was gallivanting in Russia and even taking photo ops with foreign political leaders.

This tells me that Prigozhin thought he had some insurance, something that would keep Putin from killing him even if he became useless. Something that would keep Putin from going after him no matter how much he wanted to do it. Information maybe, as some news outlets have claimed (maybe something that would seriously damage Kremlin’s standing with some of the new remaining non-enemies), or perhaps Order 66 that would trigger if he dies. Both of these were floated in the media, but for our purposes it does not matter what he had. It matters that he — and his henchmen — believed it would be sufficient to keep them alive. This would make Putin’s promise to spare him credible.

So now there are two possibilities:

- Putin found a way to neutralize the insurance. Maybe someone betrayed Prigozhin. Then the killing will naturally follow as soon as possible to organize. After all, this is what Putin wants.

- Someone wants to harm Putin and kills Prigozhin in order to either trigger the release of insurance or, if that doesn’t exist, make everyone believe Putin did it — and since Putin didn’t actually do it, cause suspicions in his inner circle.

Ukrainians would fit the second but it appears very unlikely they could’ve executed the assassination (bomb on board, maybe, missiles no way).

I’m thinking FSB. They can do it, they hate both Prigozhin and Shoigu. They could benefit from Putin thinking maybe Shoigu did it. They would benefit from rift in military as well, especially now that Shoigu seems to have concentrated more power after the mutiny. Putin’s rule depends on balancing competing interests, and since the mutiny the military has been getting stronger: Shoigu has removed generals critical of him with or without pretext, destroyed Wagner, and has been building an alternative, Redut, loyal to him. This would make FSB extremely nervous, so by killing Prigozhin — which they know Putin would not do — they create a situation in which there’s lots more discontent with both Shoigu and Putin. There are elements in the military quite sympathetic to Prigozhin’s message. FSB can execute such a plot. This is what they do. Weakening Shoigu might have been a reason enough, especially if they can avoid suspicion. FSB will likely control the investigation, so expect some nonsense about “accident” or “Ukrainians” that nobody would believe…

So maybe, just maybe, it wasn’t Putin after all… This could explain the late-night rush to the Kremlin of his cortège after news of Prigozhin’s death broke out. If Putin was in that cortège, why would he need to suddenly rush to the Kremlin from Kursk (where I think he was at the time)? An emergency after a planned assassination?

Obviously, this is speculative. I am trying to make sense of all the known facts with a story that does not require people to have been especially dumb. Not sure we will ever know, but what matters now is how the relevant people in Russia interpret this & what they do.

Purge of Potentially Unreliable Officers at MOD. Shoigu’s purge began with General Surovikin, who disappeared right after the mutiny. Surovikin was eventually relieved from command of the Air and Space Forces, but was not not been retired and appears to retain some sort of position at the Defense Ministry. Speculation had been running wild about his fate. It’s not even clear what his role might have been in any of this because all public info is of the sort “well, he was the only one who would communicate with Prigozhin” or something like that. At any rate, as Shoigu began to remove challenges to his authority at MOD, he is probably using this to reduce some of the corruption (or, more likely, redirect it to his own cronies). Surovikin could have been caught in this because I recall reading that he and his wife had unusually lavish lifestyles too. (I might be wrong about this since I did not save the article.)

The fact that he was not quietly dispatched in an accident or retired from the military is telling me that perhaps his crimes are more mundane than having somehow participated in a mutiny. Since he’s not charged with corruption/theft, as one would expect if he had been implicated directly, it might be that he wasn’t particularly egregious in that either. So it could all be just the old mafia-style redistribution of resources.

Purge of Officers Critical of MOD. While Prigozhin was busy staging a mutiny to redistribute resources within the Kremlin under the pretense of demanding changes in the military command, the true problems in the Russian military only got worse. The high command abruptly dismissed General Ivan Popov, the commander of the 58th Combined Arms Army, which is currently trying to stop ZSU’s advance in Zaporizhzhia. He is reportedly currently in Syria.

Popov recorded an audio message explaining the events that lead to his dismissal, and — this is important — the audio was publicized by General Gurulev, who is currently a member of the Russian parliament, and who frequently appears (sometimes clearly not quite sober) on popular propaganda TV shows. That is, Popov’s message was amplified by a retired general, which might indicate that there is a lot more people discontented with Gerasimov & Shoigu than Prigozhin and Girkin.

Here’s a translation of a fragment of his message:

“A difficult situation with the leadership emerged. It was a choice between remaining silent and afraid and saying what they wanted to hear, or calling things for what they are. In your name, in the name of all perished comrades-in-arms, I didn’t have the right to lie. Hence I named all the problems that exist today in the army regarding operations, supply. I pointed the attention to the most important tragedy of the modern war — the lack of counter-battery fire, lack of artillery reconnaissance stations, and mass casualties and injuries of our brothers from enemy artillery. I also raised a number of other issues, expressed them to the highest levels, did it openly and very brutally. Due to this, the seniors likely felt some danger in me and instantly, in one day, put together an order to the Minister of Defense and got rid of me. As many commanders of regiments and divisions said today, our army was not broken through the front, but our most senior commander hit us in the back, thus treacherously beheading the army in the most difficult period.”

This supports all the things that we’ve been saying about ZSU’s methodical grinding of the Russians in the south. Constant artillery fire (which is why we had to send cluster munitions), very effective in killing very large numbers of VSRF personnel, which means that fortifications will be a lot harder to defend.

It’s interesting that Popov credits himself with preventing ZSU’s breakthrough, which ignores the fact that the forces at his command are being pulverized precisely to effect that breakthrough, but voices the “stab in the back” idea, which might become the excuse to get out of the war.

When the decision to withdraw comes, it might sound roughly as follows, “We were never defeated in the field despite all of NATO and the West fighting against us. But the heroic Russian soldier was stabbed in the back by incompetent high command of grifters and corrupt degenerates, which did not supply the soldiers with enough arms and ammo, and causing their needless deaths because they still tried to fulfill their duty to the Motherland. The new leadership made the difficult decision to end hostilities in order to preserve the armed forces of the Russian Federation and to deal with the grave internal problems created by the criminals at the top.”

Silencing of Hawkish Kremlin Critics. On July 21, the FSB arrested its former employee, war criminal Girkin, and charged him with calling for extremist activities. He pleaded not guilty, was denied bail, and is currently cooling his heels in pretrial detention for two months. He was again denied bail two days ago after his lawyers made an appeal because his health had deteriorated. We had been speculating for a long time why Girkin was allowed to be so outspoken in his criticism of MOD and, recently, of Putin himself. Whatever it was, it seems to have stopped working. The arrest also seems to have achieved the desired effect: the Z channels have notably decreased their whining about the ineptitude of the government and MOD, and are limiting themselves to posts describing heroic, but often unsuccessful, defenses, letting readers draw their own conclusions. Some have started peddling pro-Shoigu stories as well.

Against these events, we were recently treated with the implausible claim that some hawks are pushing Putin to start fighting “for real” by declaring a state of emergency and unleashing total mobilization, and so on. But who are these mysterious hawks:

- nobody seems to have heard of them

- no hawks showed up in support of Prigozhin’s mutiny

- Shoigu ousted Wagner from Russia, and seems to have gone under anyone suspected of disloyalty

- army critics like Popov have been muzzled

- political critics like Girkin have been imprisoned

So how exactly is this thing supposed to work?

Nobody is pressuring Putin to escalate the war. If anything, the opposite is likely true. This leak is basically the new version of the nuclear threat: if you don’t make peace now, the situation will get so much worse.

Russia will need a new round of mobilization. But that’s just to keep the war going. They can’t turn the tide of war anymore.

In the next section we will discuss the international aspects of the war, especially in light of Kyiv’s growing confidence that it can take at least some part of the war to Russian territtory.