August 30, 2023

It has been quite some time since my last comprehensive update here, and my excuse that I have been quite active on FB and Twitter/X with analyses, and got a bit used to the shorter form. Nevertheless, this seems like a good time to take stock of what has been going on in the war, both on the front and in the rear. There is a lot to write about, so I will split this into several parts.

The last weeks saw a spate of articles in the West that breathlessly intoned that the offensive has failed, that it would not reach its objectives, that Ukraine is losing too many men, and that the time has come to freeze the conflict and negotiate. No, I am not referring to the exact same arguments that appeared at the end of the summer last year just before Ukraine’s huge breakthroughs. These are brand new arguments that just happen to say the same thing. And they come from the same sources. So let’s first deal with the idea that the offensive has failed.

Strategies of the Offensive

The offensive has not failed. In fact, it’s progressing although not according to initial plans. As I wrote in my last update in early July, after initially trying for a quick breakthrough a-la Balakleya, and failing in that, Ukraine switched to a deliberate strategy of attrition which involved stretching the Russians as much as possible, interdicting their logistics and command, attriting their artillery and air support, while methodically clearing the vast minefields they had laid. This strategy is slow and unflashy but it conserves personnel and it works, as we shall see.

The Western press came out with some claims (made by anonymous US government officials) about how the Pentagon has clashed with ZSU over the strategy of the offensive. Apparently, the Americans are unhappy with the Ukrainians not massing troops for determined push in one point (e.g., at Robotyne) but are instead attacking in several directions. The article claimed that the Americans had urged Ukraine to do so and accept that it will be very costly. They also appear to want Ukraine to follow the combined arms training they received from the West instead of their current tactics. To this, General Zaluzhnyi is said to have replied, “You don’t understand the nature of this conflict. This is not counterinsurgency. This is Kursk.”

I am having trouble believing that this sort of advice could be pushed by our military. The last time the US fought a war that remotely resembles the war in Ukraine was in Korea, over 70 years ago. Our military doctrine is predicated on achieving air superiority. In our last wars in the 21st century, we obliterated the opponent’s defenses before launching ground assaults. We had no extensive minefields to plow through while being under constant surveillance by drones and bombardment by artillery. We did not have to deal with recon drones discovering massing of troops within range of enemy fire. In short, we have no experience in this kind of war.

Now, even allowing for all of this, I cannot see the US military proffering advice that borders on malpractice. (And given some other bright ideas like “Ukraine should be using fewer drones and relying on ground troops for recon,” I rather think the source the press is using in Washington is some summer intern flunkie.) You see, nobody attacks in just one direction. Doing so makes you predictable and allows the enemy to concentrate its forces for effective defense. The Russians have a lot of troops in Ukraine, and if they could guess where the hammer will fall, they will make sure to be ready for it. The proper strategy here is to be unpredictable: feign attacks in several directions, maybe push in a few more seriously to keep the enemy guessing. This is what I called the “stretching” part of Ukraine’s strategy. The Russians have to defend along a very long front, and in the South alone it stretches for hundreds of kilometers. The Ukrainians really need to break through in just one point, and there are several that would do the job. Ukraine attacked all of them, and is currently pressing very actively two, as we shall see below, with a potential to resume advance at a third.

The Russians do have many troops, but they do not have an infinite number. In fact, we can see that they are already stretched to the limit of their currently mobilized forces: they have been frantically withdrawing units from the north (Kreminna/Lyman sector), from the west (Kherson), and even from the east (Bakhmut), in order to stem the Ukrainian advance in the South. In at least one known such instance, the attempt to transfer the 108th Guards Airborne Regiment (an elite unit) from Kherson to Robotyne ended in disaster when ZSU detected it and attacked it with HIMARS. Between a third and a half of the men were killed (230-350 troops), and between 30 and 50 deserted rather than go to the front. Credible accounts also say that the Russians have activated their operational reserve, meaning that the situation is very dire. Just today, General Gurulev (Ret) — who is also a member of the Russian Duma — appeared on Solovyev’s show to argue that the time is perfect for a nuclear strike on Robotyne. One should recall that according to Russia’s illegal annexations, this is supposed to be part of Russia that the general wants to nuke. The situation is so critical that the man who regularly calls for nuking Western capitals has now been reduced to pushing for nuking his own country. (For the record, the probability of the Russians using nukes in this manner is somewhere between 0 and vanishingly small.)

The stretching strategy uses geography against the enemy, and it can work here because the Russians are defending from the outside of a semicircle while the Ukrainians are inside. Their logistical lines are much shorter, and they have the advantage of initiative because they get to pick their axes of advance while the Russians have to guess them. The Russians themselves cannot afford to be predictable because the moment they obviously weaken one sector, they give ZSU the opportunity to strike there. (This is why they have focused on withdrawing troops from the North, where ZSU is content to sit on the defensive, and the East, where the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam gave the Russians some respite from ZSU attacking in large numbers for now.) The optimal strategy for both belligerents is to attack/defend multiple points — we know this from the famous Colonel Blotto games. In these zero-sum games, the opponents decide how to allocate their scarce resources across multiple battlefields, and success at any one of them is determined by the relative sizes of forces committed to it. The optimal strategies usually leave some potential battlefields without any troops by either side (as is the case here), but they always commit troops to multiple battlefields. Moreover, the solution is in mixed strategies — meaning that the precise allocation each opponent chooses will not be predictable by the opponent (this is a standard result in zero-sum games). While I understand the point of massive troops for a decisive breakthrough at a Schwerpunkt (center of gravity) — otherwise one risks being defeated in detail — this can only be accomplished once the Ukrainians breach the defenses on a wide enough front.

Stretching the enemy, however, is not enough. Their ability to defend must be degraded as well, preferably to the point of debility, like the US did in Iraq, but when this is not possible, as much as one can. Russia’s largest advantage in this war has been artillery, and naturally the Ukrainians have focused their attention on destroying as much of it as they can as well as blowing up ammunition depots, logistical connections, and — whenever possible — command staff. By all accounts, they have been extraordinarily successful in this. The Ukrainians have been able to achieve local superiority in artillery in specific sectors, turning the lives of the Russians defending there into a fairly decent imitation of hell. Multiple videos from Russian troops on the front show them complaining that they are pinned down in their trenches for days, that no counter-battery fire seems to ever come from their side, that attacks to capture some small objective are extremely costly and mostly pointless because the Ukrainians quickly recover whatever they manage to take, that they are forced to live with dead and dying comrades in the trenches without medical help and, increasingly often, without food or water, that they have to pay to be evacuated even when they are wounded, that commanders refuse to let them go because they are afraid they won’t come back after recovery, and that sometimes the commanders would shoot them for refusing to attack when told. Some of these problems are due to endemic corruption in VSRF, but most are really caused by ZSU interdicting their supply lines, suppressing their artillery, and keeping them pinned down.

The Russian Defenses

Before discussing the current situation on the front — and what ZSU’s strategy is accomplishing — let me briefly refresh you with what the Ukrainians have to deal with. Due to the inexcusable delays in Western military aid, the Ukrainians were forced to repeatedly postpone their offensive until the summer got so late, that they simply had to launch it or risk not having enough time before the rainy fall makes offensive operations very difficult (probably early October). The Russians used this time well: they mobilized more troops (to the tune of 20k-25k per month), and the built very extensive fortifications in all areas where ZSU could be expected to be considering for a breakthrough. The deeply echeloned defense consists of three “lines.”

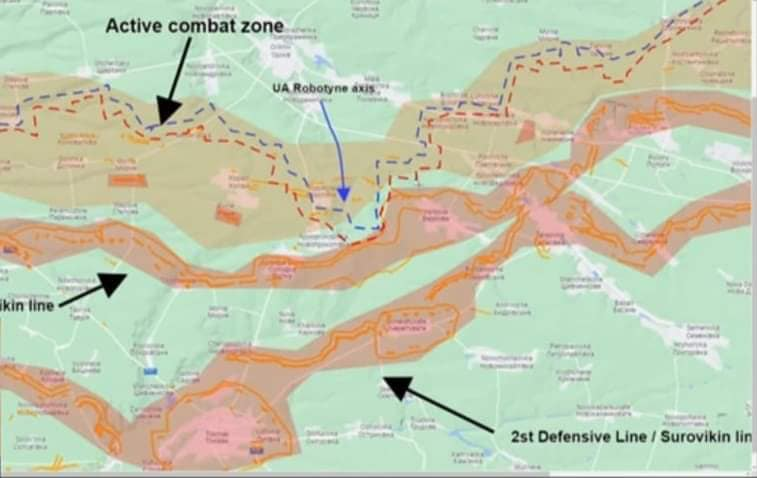

The first is the “active combat zone” and comprises extensive minefields that slow down the Ukrainians who cannot advance in any great numbers before clearing them. When they attempt to clear them, drones direct strikes, with Russians coming forward, attacking, and then retreating before the Ukrainians can counter. They can afford to retreat because they know ZSU cannot exploit this due to the minefields. To say that these minefields are massive would be an understatement. The Russians have mined, remotely and with sappers, all roads, then the areas around them that Ukrainians could attempt to use to avoid the roads, and all tree lines (also often equipped with defensive positions). They have laid a mix of anti-equipment and anti-personnel landmines, and sometimes they even stack them on top of each other. The extent of coverage and its saturation is hard to fathom: the Russians have hundreds of millions of mines inherited from the Soviets, and mines are very easy and cheap to make, so they have put them everywhere ZSU could potentially come through, with a density that sometimes reaches 8 mines per square meter. That’s EIGHT mines per ONE square meter, with an area the size of Florida. The mines are often difficult or impossible to detect due to high vegetation. The Ukrainians have developed some innovative ways of discovering mines (e.g., using drones to detect their heat signatures at dusk) but in general they have to move very deliberately through these as there is simply no way around them.

The Ukrainians do not have enough equipment to clear the fields quickly (although the West is supplying more) and they seem to have underestimates just how extensive these fields were — this is what they learned after a few days of attempting to Blitz their way through the Russian defenses. The point here is that when you see the “Surovikin Line” of systems of trenches and “dragon’s teeth,” you are looking only at a part of the echeloned defense, and arguably not its most important part. If VSRF succeed in keeping ZSU from penetrating these fields in large enough numbers, then the fortified second line will have a much easier time halting them. If, on the other hand, ZSU breach the first line on a wide enough front so that they can concentrate enough troops to attack the static positions, then these will almost certainly fall. The Ukrainians have spent 3 months getting through this first line, but it should be now clear that success in this makes a breakthrough very likely (I expect over the next 2-3 weeks).

The importance of the active combat zone is why many people (including me) refer to it as a proper line of defense while some analysts only count the static fortifications, as in the figure below. When it comes to these, the second line (“first defensive line” in the figure) is a system of trenches, concrete bunkers, and fortified positions, reinforced with anti-tank installations (“dragon teeth” and ditches), and so on. This has far fewer mines because the defending troops manning these fortifications must be able to get supplies and reinforcements and evacuate the wounded. All such defenses can be overcome if the attacker commits sufficient forces and the defenders have trouble with lack of personnel or ammunition.

The third line (“second line” in the figure) is where reserves sit, and it’s generally the Hail Mary part of the defense: if the Ukrainians get to that, it would be exceedingly difficult to hold. This line is the support for the second and the first. Of course, in practice there is no magic number 3 to this: the Russians have been furiously digging new fortifications further south, with the intention of turning the third line into yet another supported one that ZSU would have to overcome. However, because they have so many troops between these lines, the Russians cannot put landmines in sufficient quantities to make them as big of a problem as the first line. In an important sense, breaching the first line and bringing through large numbers of troops would mean a Ukrainian victory in this campaign.

Defining Success for the Offensive

This brings me to something we need to define: victory. What would constitute success or failure in this offensive? As I have explained before, from a political standpoint (and prospects for war termination), the unanswered question is whether ZSU can dislodge the Russians from occupied territories by force. The Russians have bet everything on holding them until Western support for Ukraine erodes, so the Ukrainians must demonstrate that this strategy is unlikely to work. With the West being somewhat flaky (especially with looming Presidential elections in the US next year, when both the main GOP candidate and the bevy of nearly-insane contenders promising to cut aid to Ukraine), the strategy must be proactive: push the Russians out.

The most promising direction for this is the South because this is where the Russian supply lines are vulnerable. While they can supply Luhansk and Donetsk from the interior of Russia over short land routes, supplying the forces in the South can only be done through the “land bridge” in occupied Zaporizhzhia or the Kerch Bridge that connects Crimea to Russia. If the Ukrainians succeed in cutting the land bridge, they will isolate the troops to the West of it, making their position untenable much like they did with the grouping in occupied Kherson. The Russians would either have to withdraw them or attempt relief.

The Russians could try to supply everything through Crimea. But this will run into trouble as well, for two reasons. First, the Ukrainians have shown, repeatedly, that they can hit almost any target in Crimea they want to (most recently, they even sent a raid party there and destroyed components of S-400 AD system). Among them, the bridges at the neck of the peninsula, not to mention the Kerch Bridge. Second, the Russians still have to supply the nearly 2M civilian population on Crimea, and then it will be down to the Kerch Bridge for both military and civilian needs. I am not sure they can handle it, and with the Ukrainian sea drones lurking about, also do not know just how reliable ferry services they can organize. The Russians appear to have sunk barges on the approaches to the Kerch Bridge, and have likely strung cables between them to protect from sea drones, but it’s unclear how effective this is going to be, not to mention that once ZSU gets longer-range missiles, the bridge will become quite vulnerable.

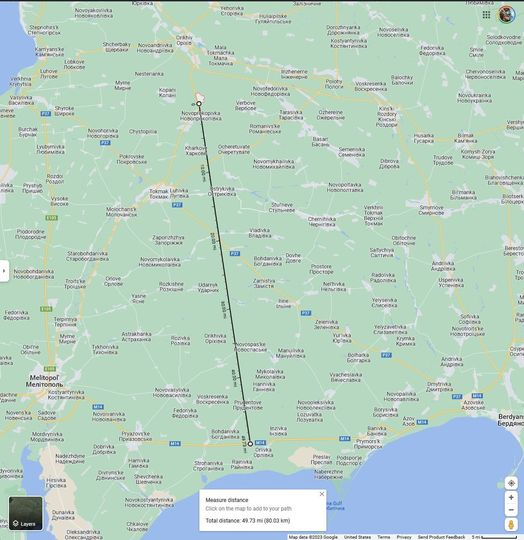

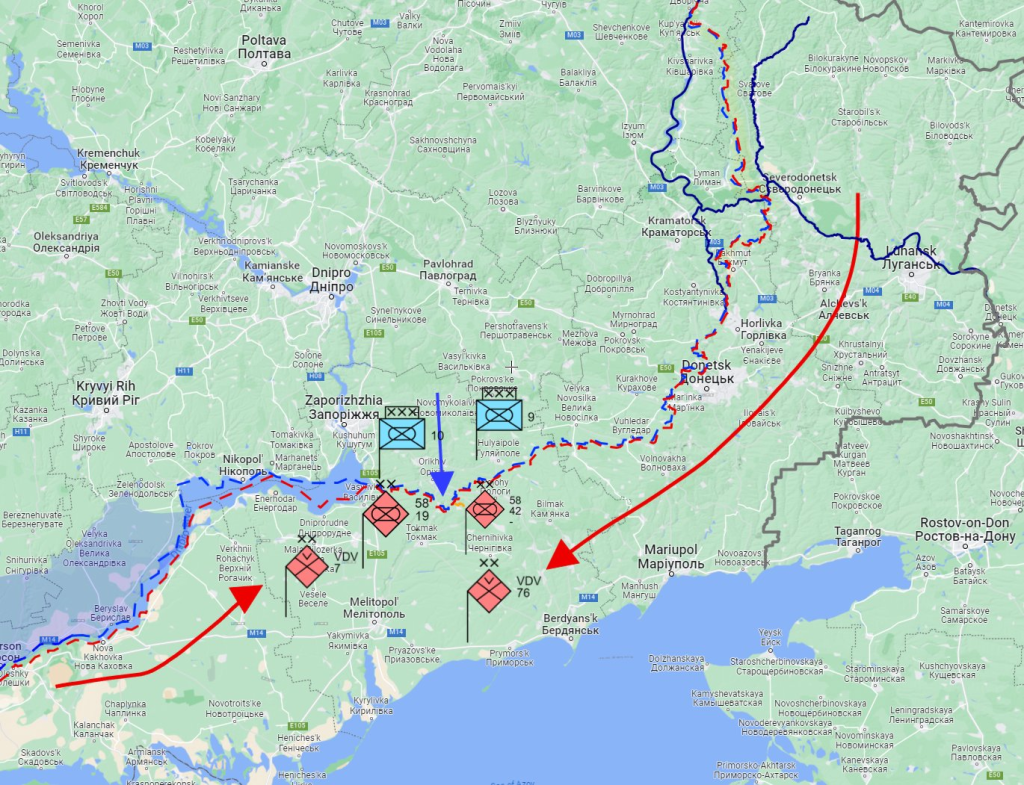

Thus, in order to dislodge the Russians from a sizeable chunk of land, the most promising strategy is to cut the land bridge, not assault them head on. The are very few rail and road connections between the front line and the Azov Sea, as seen on the map. There are two key hubs at Tokmak and Melitopol in this sector of the front. Tokmak is the intersection of P37 that runs between Vasylivka and Berdyansk, and Melitopol is the connection between Berdyansk and Crimea along the M14. It’s important to note that the Russians have been using commercial trucks for their transport needs, and M14 is the southernmost viable route. This means that in order to interdict these supplies, ZSU have to take M14 under consistent fire control, at the very least. Doing so would make it very risky to run trucks, which means the trucking companies will either quit or raise prices, not to mention suffer losses of trucks and drivers. The government can, of course, compel them to work but if they cannot keep up the volume, this will not be sufficient.

The offensive’s most ambitious goal would be reaching the Sea of Azov. I do not believe this is possible in the current offensive. The next target would be reaching Melitopol — this would position ZSU straight on top of the M14 and the rail, meaning nothing would get through. It is not necessary to liberate Melitopol for this either. According to an anonymous Washington source, Melitopol was indeed an original goal of the offensive. I do not know if this is true although it does make sense. The assessment they offered is that ZSU would reach within a few miles of the city but not be able to liberate it. In all honesty, I think this assessment is very optimistic as it depends entirely on the Russian defenses crumbling unexpectedly, and progress becoming nearly unimpeded. For all the problems I enumerated above, I see no evidence of the Russians just melting away. Their resistance is tenacious, determined, and very serious. For all the low morale, they have enough unaccountable commanders and blocking troops to make sure their mobiki are more afraid of them than the Ukrainians, and do not run. Thus, while reaching Mariupol would constitute a clear success (provided it is accomplished with acceptable losses), I am leaving this as a hoped-for-but-not-very-likely-this-year scenario.

The third goal, which is also the minimal one required to consider the offensive successful, would be reaching Tokmak. One the map above, I’ve indicated the distance from the front line a few days ago (it has advanced south since) to M14 — about 80km — which is the range of HIMARS with the missiles currently supplied (we could give them longer-range ones). Besieging or liberating Tokmak would bring ZSU southward enough to force the Russians out of a large sector around it (since supplies will get very hard), but, more importantly, it will bring large sections of M14 within range. When this happens, it will be up to the Russians to see if they can keep supplying their troops on the left bank of the Dnipro in Kherson. Obviously, if they choose to withdraw into Crimea there, this will be a huge success for the Ukrainians.

Note that this is just the Orikhiv sector and Tokmak direction of the front. As explained below, there are possibilities east of it, at the Velika Novosylka sector, with Berdyansk direction.

Assessment of Current Progress

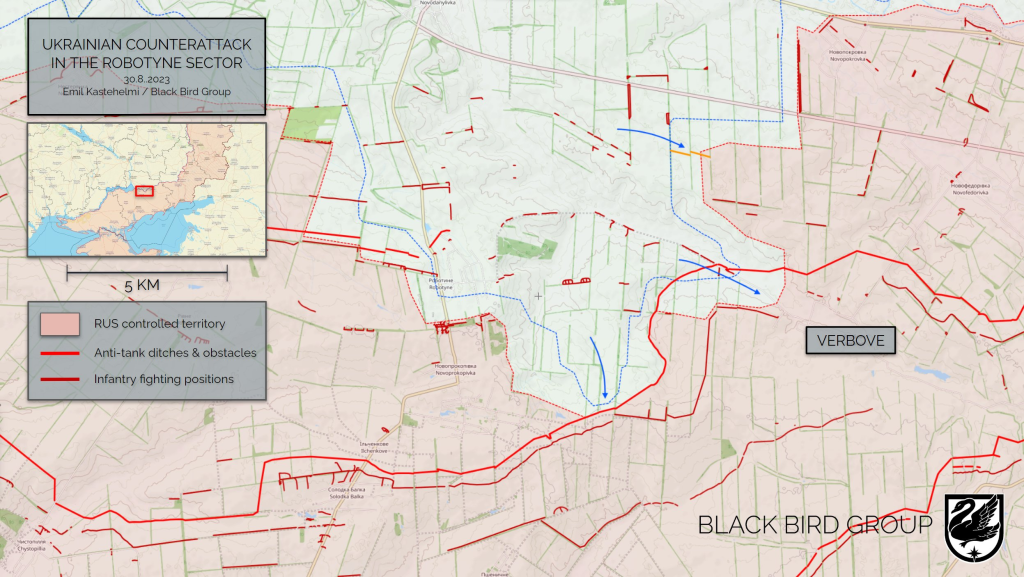

Let’s start with the hottest sector we just discussed: Orikhiv, direction Tokmak. After the extremely heavy fighting for Robotyne — people do not seem to realize that the two sides committed here larger forces than at Bakhmut — ZSU liberated the town, effectively breaching the first defensive line described above. They advanced south and southeast of the town several days ago, where they engaged the second line (the first of the Surovikin Line). They spent the last few days gradually widening the line of contact along two axes, and today they were geolocated on the outskirts of Verbove to the east. This is far behind the first Surovikin Line, and while it is unclear how extensive the breach is (it could be a reconnaissance unit), indications are that the situation there is critical for the Russians (per their channels).

It is important to emphasize that this is a breach, not a breakthrough, but this is a rapidly developing situation that might well turn the Russian defense in this sector and provide the conditions for a breakthrough. Verbove is a tough obstacle as it sits in a valley and the Russians control the heights. (Incidentally, this was where the ill-fated 104th Guards Regiment was supposed to deploy.) One should still keep in mind though that ZSU are constantly shifting the direction of their efforts, surprising the Russians (and analysts) on multiple occasions. The key question here is how many reserves the Russians have available to defend the Surovikin Line in this sector. It is clear that whatever their original estimates were, the forces they concentrated in Zaporizhzhia have proven to be insufficient, forcing them to cannibalize other sectors. The Russians also appear to have orders not to give up any settlements, no matter how strategically insignificant. (My guess is that this is a combination of reluctance of local commanders to report losses, and concern among high command that a stream of news items saying “ZSU liberated town X” and “ZSU liberated village Y” will create a momentum of increasing worries among troops that could easily spark panic that can turn into runs, precipitating a rout, as it happened in several instances last year.)

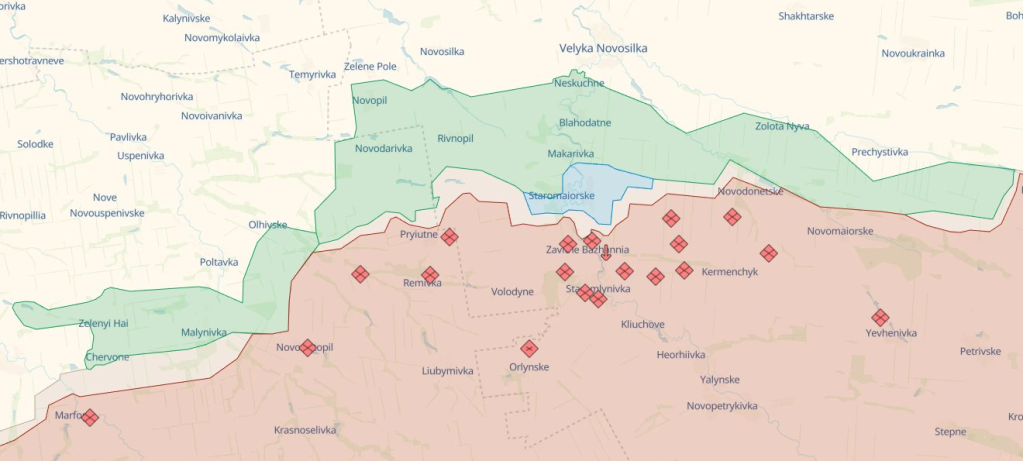

Velyka Novosilka sector, Berdyansk direction. With all attention on Robotyne, people sometimes forget that ZSU are actively pushing here as well. After liberating Staromaiorske and Urozhaine, ZSU has steadily enlarged their incursion into Russian defenses. Over the past days, VSRF have retreated toward the Pryiutne-Zavitne Bazhannia line. (I saw a video of ZSU taking Russian POWs somewhere near the latter, which might indicate that the DeepState map here is outdated.)

The zone of active fighting here is much wider than in Tokmak direction, with ZSU attempting to liberate Staromlynivka, which is the hub for the road from Novomaiorske (east) toward Pryiutne (northwest), Nozoslatopil (southwest), and Mariupol through Krasna Poliana (southeast). ZSU is striking toward both Staromlynivka and Kremenchyk, which would take them to the first Surovikin Line in this sector. Here, too, VSRF has been forced to commit troops from its operational reserve, but it is unclear if they can simultaneously hold ZSU in both directions. (VSRF lost Urozhaine when they could not reinforce it.) The stretching aspect of ZSU’s strategy is evident here, and the Russians are faced with the unpleasant prospects of being outflanked and bypassed.

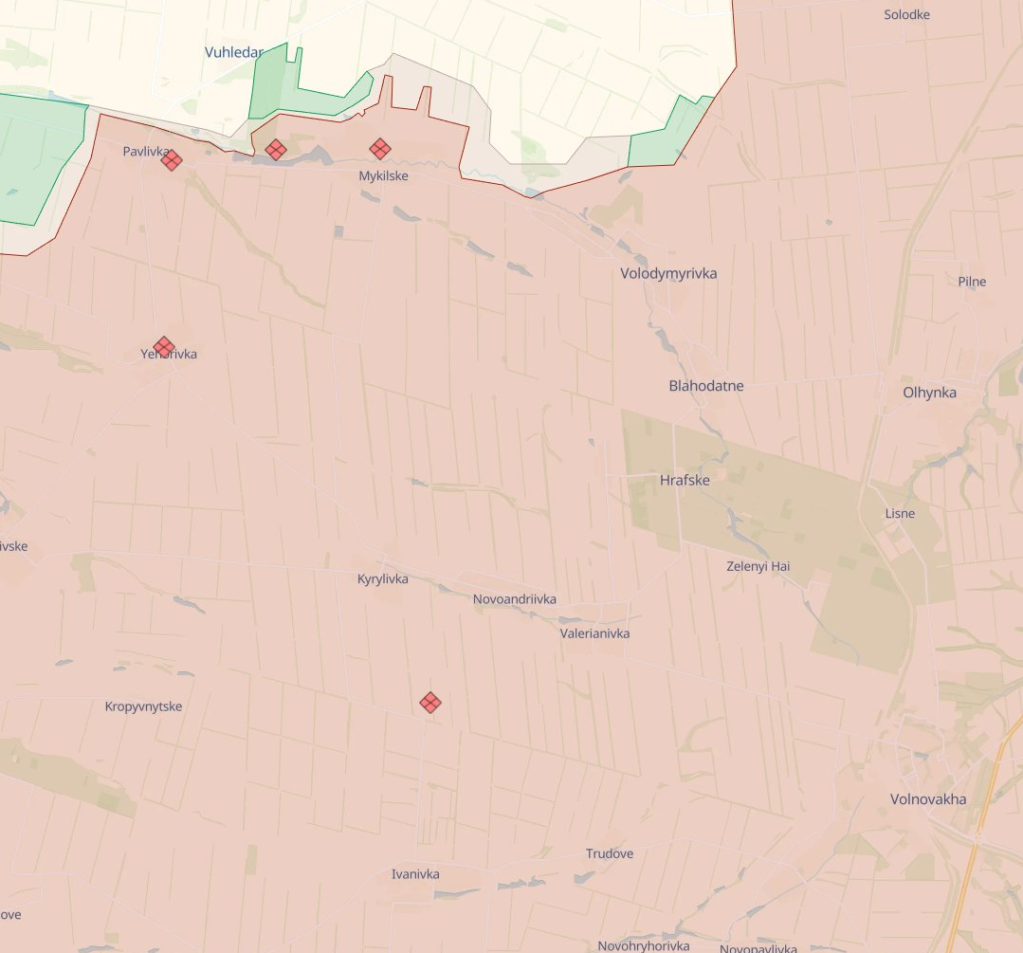

Vuhledar sector, direction Volnovakha. After the debacle of the Russian attempt to seize Vuhledar during the Gerasimov Offensive, ZSU have tried attacking toward Volnovakha. This is a tempting sector because the distance from the front line to Mariupol is only 65km. The Russians have been stubbornly defending the key villages of Pavlivka and Mykilske, trying to prevent ZSU from crossing the Kishlahach River here. ZSU’s advance has been limited although they recently forced VSRF to retreat from the western outskirts of Pavlivka.

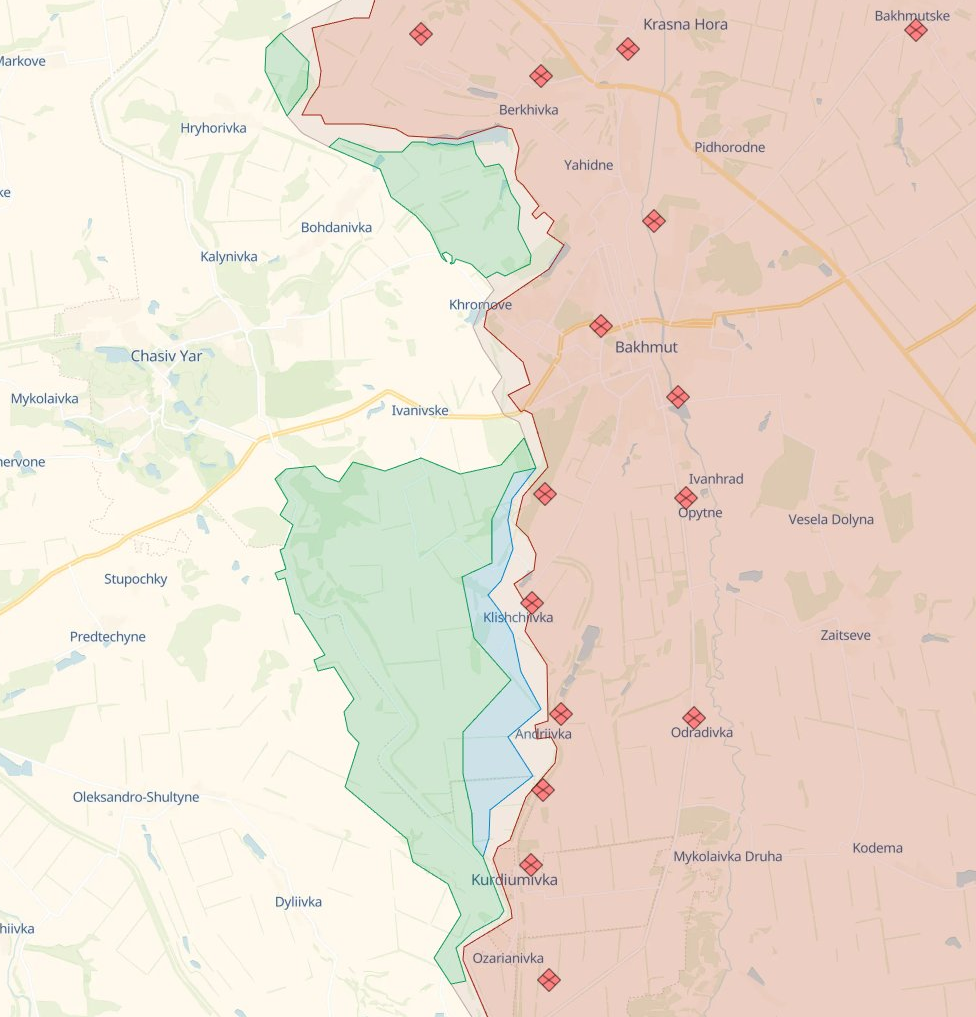

Donbas sector, direction Bakhmut. This is the battle that seems to never end. After the controversy of defending Bakhmut tooth and nail during the Gerasimov Offensive — even to the point that many online experts began to accuse General Syrskyi of everything from jealousy to incompetence — it looks like this defense can be credited as the battle that broke Wagner. This is where Prigozhin’s PMC was supposed to deliver victory, where it almost captured the town at a grievous cost of at least 20,000 men, and this is where the overt problems with Shoigu’s Ministry of Defense began over accusations of insufficient support and outright sabotage. I will discuss the coda to the Wagner Opera below, but here I would just say that without the defense of Bakhmut, there would have been no mutiny, no Prigozhin’s untimely demise, and no disintegration of Wagner, both in Russia and abroad. This, of course, is a happy byproduct of the defense of Bakhmut, not its goal.

Now the Russians appear determined to hold onto their sole gain this year nbut they are steadily losing ground even though ZSU is not committing fresh forces to this sector. VSRF have been pushed east on both sides of the city, and are currently clinging to Klishchiivka and Kurdiumivka on the road connecting Bakhmut to Horlivka in the south. ZSU’s goal here appears to begetting close enough to take under fire control the road connecting Bakhmut to Popasna without actually fighting for Bakhmut inside the town like the Wagnerites did. This is causing VSRF to stretch yet again, defending everything from Yahidne to the north to Kurdiumivka in the south. Given how important Bakhmut seems to the Russians, drawing more of their forces to its defense without detracting from the offensive in the south seems a sound strategy.

Luhansk sector, direction Kupyansk. The much talked-about Russian offensive with huge forces (100,000 men and 800 tanks) has not made any gains in a while. They have failed to cross the Oskil River but are still launching attacks toward Synkivka. About 10 days ago, Z-channels published a video claiming that it showed the capture of Synkivka, but it turned out to be a video from Voronovo near Severodonetsk from last year. In direction Lyman, they are still pushing toward Torske but seem to have run out of steam. The problem here appears to be that the Russians did not really consider this part of the front very important aside from threatening ZSU sufficiently to force it to commit resources there that would detract from its southward push. In the event, the opposite has happened — VSRF has been whittling down the offensive potential in Luhansk in order to reinforce its defenses in the south. The most recent example is the transfer of the elite 76th Guards Air Assault Division from their reserve in Luhansk. It is considered one of their best units.

As the map (made by DefMon3) indicates, Russia has also been thinning its defenses in Kherson sector, on the left bank of the Dnipro. The situation here continues to cause headaches for the Russians as well. Despite repeatedly claiming to have cleared the Ukrainian bridgehead at Oleshky, VSRF have proven unable to dislodge ZSU from the left bank here. The situation with the incursion at Kozachi Laheri to the east is less clear. Here, ZSU crossed during the night of August 8. In the ensuing battle, they captured several Russian POWs, one of them Major Tomov. They initially faked a video with Russians capturing ZSU POWs in an attempt to lure other Russians, but when this didn’t work out, they published a video with Major Tomov showing the disposition of Russian forces on a map (that’s unlikely to be useful since he’s just a local commander who probably does not know much of anything else that the Ukrinians don’t already know) and then another video with him being interrogated. The latter is interesting in that it shows what defense many Russians are likely to use after the war: temporary insanity (does not understand how peaceful people like him suddenly changed and went to Ukraine to murder for ideals they have nothing in common with). He also describes the grievous losses (30% of his unit in a single day of combat), badly prepared mobiki, incompetent command, and the hostility of the local population. The latter is a recurring theme: soldiers often describe how the locals are ready to poison them or knife them any chance they get.

ZSU regularly conduct raids across the river, harassing the Russians, and periodically panicking Z-channels that a crossing might be coming. I have seen no signs of this being true, however. Besides, the strategy in Zaporizhzhia has the liberation of the left bank without actually fighting there as one of its goals. I am not surprised that the Russians are moving units out of here. Of course, they do have to be careful because they cannot leave this sector too weak either.

Conclusion: the offensive has not failed, it is progressing. But it is slow and it is bloody, and it looks like it did not go according to plan. If liberating Melitopol was indeed, ZSU’s operational objective for the offensive, then I do not think they have good chances of achieving it. Getting to Tokmak, while disappointing in that regard, should still be regarded as a major success given the conditions under which the offensive is taking place, provided it enables ZSU to sufficiently degrade the access to Crimea by land. In either case, there will be some important lessons to learn. Some of them — speed of Western deliveries — is really not something the Ukrainians can do much about. But others — their internal staffing and command issues that have hampered coordination that could have made their stretching/attrition strategy even more effective — can, and should be, addressed. General Zaluzhny talked about these problems in his interview, and it does look like they are quite persistent.

Attrition, on Both Sides

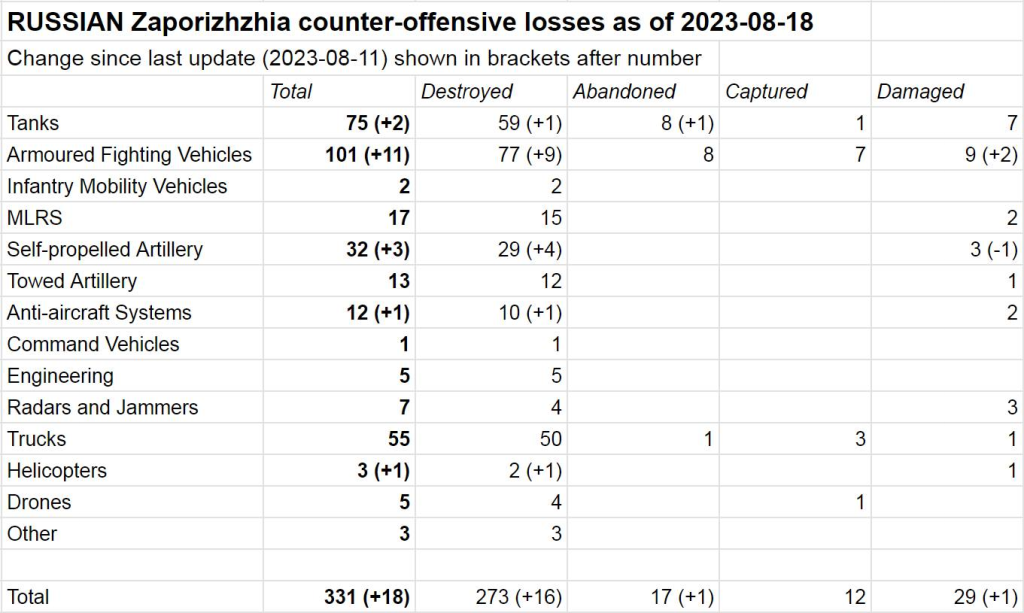

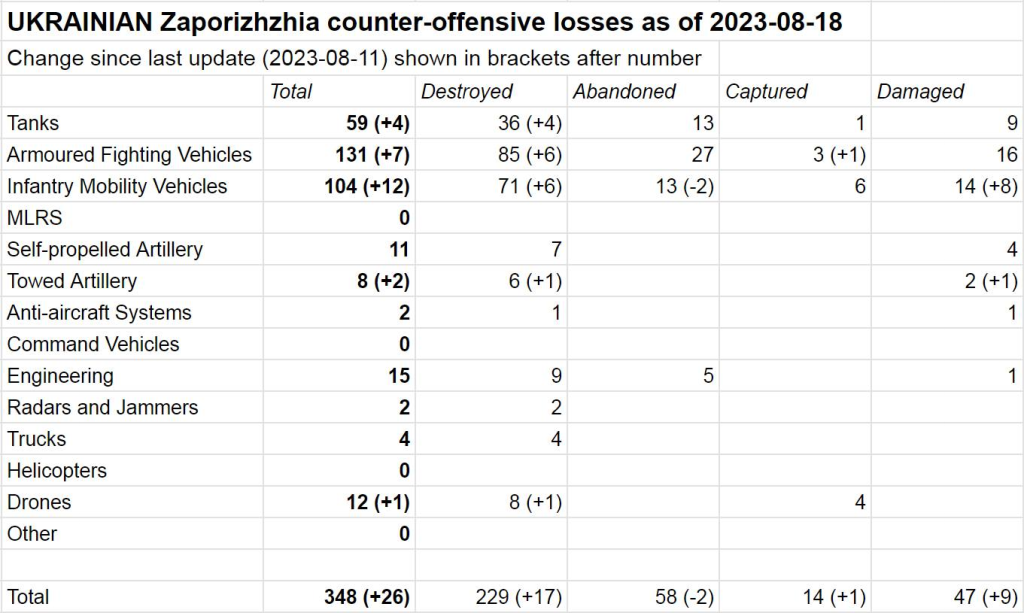

The success of the offensive will not just be measured by whether ZSU cut the land bridge and how much territory they manage to liberate, but by whether they have done this with acceptable losses. Let us first take a look at equipment. Here are the two tables with confirmed losses of equipment since the start of the offensive on the Zaporizhzhia front (the full spreadsheet is here).

Moreover, by all accounts, the Western MBTs and IFVs have proven their weight in gold because crew survivability is very high even when the vehicles themselves are disabled. For example, of the 71 Leopard 2 MBTs, only five have been destroyed so far: two 2A4 and three 2A6, with four and six of each type being damaged. Most damaged ones are repaired in Poland and Germany, but more importantly, the commander of the German contingent in Slovakia, Lt. Colonel Worgull, recently revealed that not a single Ukrainian tank crew member has died in a Leo 2A6 MBT yet. The key here is that the West must commit to at least maintaining ZSU’s equipment levels. The hardware is good.

The situation with manpower is more complicated. The one, and only, semi-official Western estimate we have was published by NYT on August 18. It says that the Russians have suffered 300,00 casualties (of whom 120,000 killed), while the Ukrainians have suffered 190,000 casualties (of whom 70,000 killed). While the estimate for Russia seems a bit low to me, it was the estimate for Ukraine that caused a lot of controversy online. I think that it’s likely correct, and might actually be toward the lower end of the possible range.

The Ukrainian military said that it needs to mobilize about 10,000 people per month to maintain its existing level of military readiness. This means several things, none of which allow us to quantify ZSU irretrievable losses with any precision despite allowing us to make some important inferences that do not require precision. The replacements are for:

- irretrievably lost: killed, missing, deserted, captured

- permanently disabled and unable to continue to serve

- wounded, who will return after recuperating (days, weeks, or months)

- rotated out for rest and recovery, and will return when this is done

I have no information about the proportion of each. The crucial factor is the number of wounded (WIA), and of these, the number of those who can return to service.

For the Russians, the ratio of KIA:WIA seems to be 1:1.5 or higher. In other words, there are almost as many dead as there are wounded. The main reason for this is very bad medical assistance and evacuation procedures, about which I have written on several occasions. Contributing factors are general lack of coordination, corruption, insufficiency of properly trained personnel, problems with supply, and little incentive to preserve soldiers. Thus, a great many soldiers die in circumstances where a Ukrainian soldier would survive.

For the Russians, the ratio of KIA:WIA seems to be 1:1.5 or higher. In other words, there are almost as many dead as there are wounded. The main reason for this is very bad medical assistance and evacuation procedures, about which I have written on several occasions. Contributing factors are general lack of coordination, corruption, insufficiency of properly trained personnel, problems with supply, and little incentive to preserve soldiers. Thus, a great many soldiers die in circumstances where a Ukrainian soldier would survive.

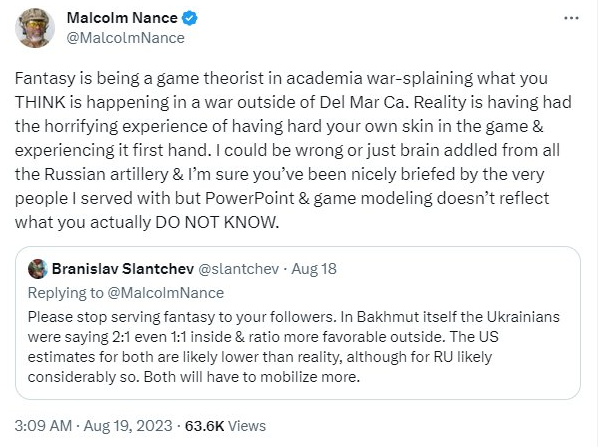

On the Ukrainian side, I recently got a lot of heat from an American who is serving with ZSU, and who took great exception to my claim that his estimate of 25,000 ZSU killed in the entire war so far was a fantasy. While he eventually acknowledged that perhaps this number is too low, his main point was interesting as it was about the quality of Ukrainian medical service.

Now, I have written about this as well, which is why I believe the KIA:WIA ratio for ZSU is 1:3 or lower (that is one killed for each 3 wounded). His example was, and I quote, “Our battalion had to take 40 guys off the line in one week in light walking WIAs but only 2 KIA in 3 months of intense combat in Bakhmut.”

It’s not likely that 40 WIA is a weekly average for this battalion as he probably gave the highest number for dramatic effect (if they took 40 guys off every week, the battalion would have to be essentially fully replaced every 3 months or so). But even if we took 1/10 of this as weekly average, we’d end up with 48 WIA over 3 months with just 2 KIA. A ratio of 1:24 KIA:WIA seems extremely unlikely to me to be representative of ZSU’s experiences overall. For comparison, the ratio for US military during the Gulf War was 1:3.15, and 1:7.25 during the Iraq War. I’m having trouble believing that ZSU, which are under way more intense artillery fire than US army was, would be able to beat the American medevac quality and come anywhere near our ratio.

Let’s be generous and assume 1:4, with 75% recovery among wounded. This means for every 5 injured, 2 are lost to the army permanently. Let’s also be generous and say half of the 10k new are needed due to rotations. This leaves us with 5,000 per month to replace losses due to injuries. With the ratio we assumed, this would yield 2,000 permanently lost per month. Over 18 months of war, we would get 36,000 just from this rough calculation. Look at how many assumptions we had to make in favor of a lower count, and we still ended up with 44% more killed than the claim above. That’s why I said it was fantasy.

The reality is that 36,000 is also a fantasy because it averages over the war without regard to intensity and operation specifics. I happen to think that the NYT number for Ukraine, 70,000, is low, but in the absence of more direct evidence, I would treat is at least as the lower bound. I very much doubt that they overestimated them.

Frankly, bandying about claims about 25,000 total ZSU dead is counterproductive because it diminishes the brutality of the war, the intensity of fighting, and the sacrifice that Ukraine is making. It injects unwarranted optimism that could both undermine the desire to provide more aid (they are doing fine) and increases the depth of disappointment when ZSU doesn’t achieve the goals such an optimist sets for them.

The losses are significant, and both sides will have to mobilize more people to replace them. This is important because it will cause strain in both societies, as even examples from Ukraine suggest. There, however, the social consensus is that the war must be won, and so it is exceedingly difficult to avoid service without fleeing abroad or risking ostracism. For Russia, where the significantly larger losses demand more people to be conscripted, the situation is not at all straightforward for the Kremlin.

In the next part, we will deal with the domestic situation in Russia.

Thanks for getting back to the long format – has been a while.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mr. Nance insists that even minor injuries result in battlefield evacuations and high quality medical care.

Let’s say that’s true: Does every such injury get counted by Ukraine as WIA? How do we know Ukraine’s WIA definition is the same as the one US officials are using?

Someone should send Nance the Wikipedia article on survivorship bias. Both because it applies here (if an entire unit is wiped out or overrun, there’s nobody to describe the battle on Twitter) and because he might rethink his disdain for academic analysis conducted away from the front lines.

Snark aside, another implication of Ukraine’s superior evacuation is that even though Russia has an inferior KIA:WIA ratio, it probably has a superior non-disabled WIA to disabled WIA ratio, because the most severe injuries ended up as KIA instead.

LikeLiked by 2 people